I don’t know if I mentioned it anywhere else, but I ended up taking a deliberate offseason from USPSA competition this winter. From about November 15 to the end of this week, I haven’t (won’t have) done any live-fire practice or any deliberate dry-fire practice. Beyond that, I’ve barely even touched my competition gun.

Why an Offseason?

Partially to give myself time for other big projects, partially to break myself of bad habits. The benefit to taking time entirely off from shooting pursuits is the brief period, upon returning, where previously unconscious things take conscious thought, and thus are malleable in a way they aren’t midseason.

In particular, it’s a good time to change equipment, and to make any tweaks to gun handling skills you want to make. And, having gotten a season of Revolver experience under my belt, there were some things I wanted to change.

Grips

The Ruger Super GP100 I shoot in competition came with Hogue hardwood monogrips. They have that Miculek-approved, sharply vertical grip angle, and look so stunning on the gun that grown men have cried.

And I had to give them up. You see, the Hogue grips, unlike Mr. Miculek’s, are opinionated. That is to say, there are contours and swells on the grip that push your hands in certain directions, and they push my hands places I don’t want them to go. Namely, they swell about midway up, then narrow, then swell again at the top. That means you can’t get an extra-high grip without the wood digging into your hand and bashing your palm in recoil.

I replaced them with a set of Altamont grips. They’re more along traditional lines of revolver grip design in two ways. One, they’re simply shaped. They’re slightly fatter at the base, and taper to a narrower profile at the top, which lets me get my strong hand high while leaving plenty of real estate at the bottom. Two, they’re a rubber center core with grip panels. The grip panels are, alas, not gorgeous, lustrous, almost luminous hardwood. They’re fairly pedestrian walnut-dyed birch laminate. I did at least hold out for a little fleur-de-lis pattern on the grips.

To really belabor the point, they aren’t as pretty as the Hogue grips, but my suspicion is that they’ll be substantially better competition grip. A bit of shock absorption from the rubber, combined with minor power factor loads out of a 45oz gun, means they should sting my hands an awful lot less than wood grips which punish holding the gun how I want to. They have a bit of texture, too, and put my thumb closer to the controls, which opens up some interesting possibilities.

Holster

We’ll get to those later, though. The next item on the list is the holster.

To get started quickly and at relatively low cost, I bought the SpeedBeez Kydex holster. At the time, it was the only one in stock which I could guarantee would fit the GP100. It was perfectly serviceable, and cut down low enough in the front so it didn’t interfere with fast draws. It probably wasn’t holding me back in any way, and I still think it’s a good product, which is why I’m keeping it in my box-o-shooting-stuff.

But Revolver is a race division in USPSA, so I’m allowed whatever kind of crazy holster I want, as long as it covers the trigger guard and holds the gun so that it points less than three feet away from my feet. It just so happens that our very own parvusimperator was looking to ditch his Double Alpha Alpha-X, and let it go at a very reasonable price. I sold the the Phoenix Trinity insert block he bought it with, got a Smith and Wesson N-frame block (the DAA website now lists the GP100 as compatible with that one), and added the muzzle rest kit for good measure, along with a 3D-printed muzzle support adapter.

The holster works well. Parvusimperator’s quarrel with it is that it can lock up on the gun if it’s pulled at a bad angle, which can happen under stress. The muzzle rest, which I got mostly because guns with round trigger guards, like my revolver, can rotate forward and back slightly in the holster, ended up solving the problem. Since the muzzle sits on a little peg, the muzzle rest constrains the angles at which you can pull the gun free, preventing it from binding before the insert block lets go. Plus, the muzzle rest gives me a target to aim at when reholstering, saving me the embarrassment of fishing around for the right angle after a stage.

Is it faster? Maybe incrementally. The best draw I’ve ever put on the dry fire timer is 0.78s, shooting at a target at a scale distance of about two yards, which is about a tenth faster than I could manage with the SpeedBeez holster. Drawing to a shot that poses even the slightest challenge, I’m up around between 1.0 and 1.2 depending on the shot and the draw, which is exactly where I was with the SpeedBeez one.

The Triple Alpha X, as one of those trigger-guard-only holsters, has nothing around the cylinder or non-trigger controls. This freed me to tackle another project that’s been on my mind.

Cylinder Release

Either I have short thumbs, or the people who design magazine and cylinder catches have extra-long ones. I don’t think I’ve owned a single handgun where I can reliably hit the ‘add more ammo’ button without breaking my grip in some way.

You’d think this wouldn’t be a big deal, given my preferred revolver reload technique, which involves letting go with my strong hand altogether. We’ll circle back to that. I still wanted a big fat paddle cylinder release.

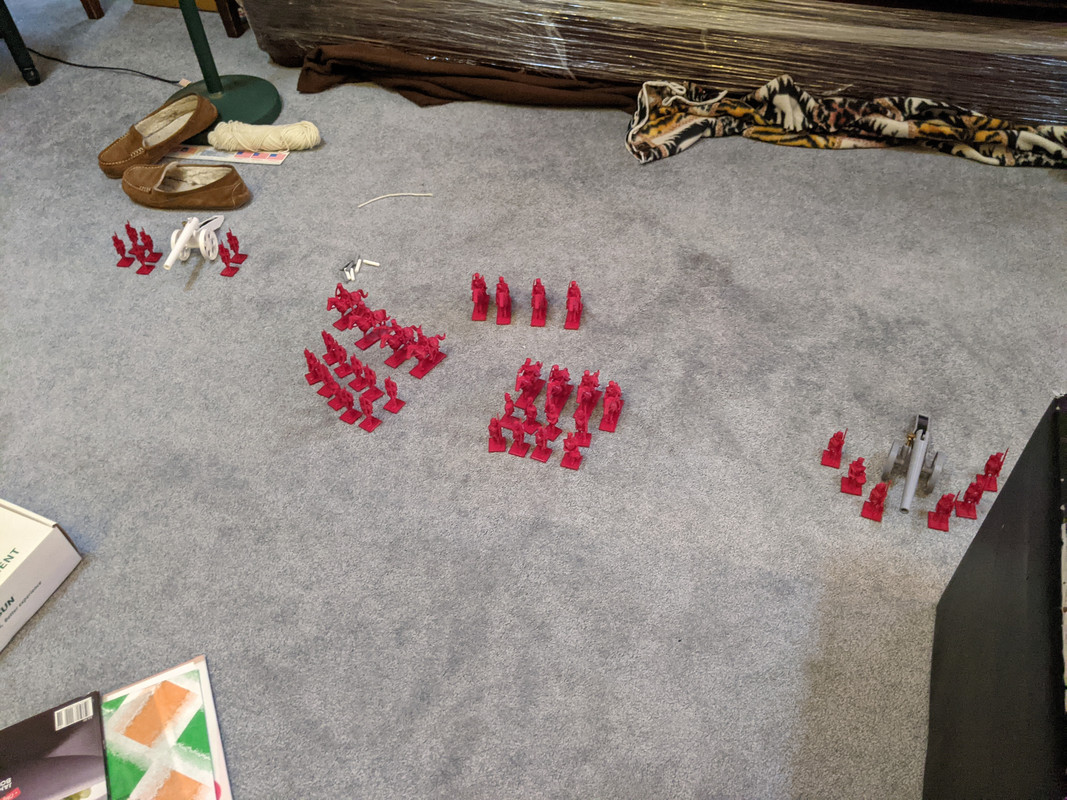

Nobody makes one. I mean, certain gunsmiths do (David Olhasso, out in eastern PA, will do one for you, if you can get the gun out to him), but there’s no drop-in replacement, which was tremendously vexing. Or it was, before I bought a 3D printer. After that purchase, the lack of a part I could buy ceased to be a vexation and became instead an item of unfinished business.

A few hours with calipers and CAD led to my banging out in a weekend what Hogue, Ruger, et al. haven’t managed to do in a few decades: a functioning extended cylinder release for GP100s. The one in my gun right now is printed in pretty bog-standard PLA+, and surprisingly, that’s proven enough to stand up to relatively intense dry fire. It took a dozen and a half prototypes, but I finally have one which is both functional and ergonomic.

There’s a lot that went into the design, which might get a post of its own, but on ergonomics, suffice it to say that I can hit the cylinder release with my strong thumb without moving my hand at all. This is obviously a vast improvement.

On function, I’ll leave it at this: I think a plastic part, though it might seem a bit chintzy, is actually going to be sufficiently strong to stand up to real use. The only thing that touches the cylinder release during the firing cycle is the spring-loaded pin that runs through the cylinder to unlock the front latch. All it has to do is bear that impact, from endshake, with a spring to help out. PLA might have heat problems, and it might be a bit too brittle around the pivot, depending on how hard the cylinder hits it. All that being said, I think some kind of engineering nylon will probably be perfectly adequate, and I have a sample or two on the way soon, hopefully.

Reloads (technique)

Earlier, I hinted at some changes to reloading technique, and here we are.

I have hitherto been an advocate of the strong hand reload, favored by one Miculek, as well as about half of the top 20 on the USPSA Revolver leaderboard and the current champ. Let’s assume you’re right-handed for the rest of this section, so I don’t get my strong and weak hands confused.

The strong hand reload starts with moving your left hand up to the cylinder, while your right hand hits the cylinder release. Your left fingers push the cylinder open into your left palm, and your left thumb hits the cylinder release. Meanwhile, your right hand goes to get a new moon clip. Your left hand brings the gun down to your belt, your right hand drops the clip in, and you rebuild your grip on the way up.

The strong hand reload has a major advantage amidst all the gun-tossing between hands: both hands are pretty much always occupied. There’s no dead time. It’s also relatively easy to do (though sometimes in compromised fashion) no matter which direction you’re moving.

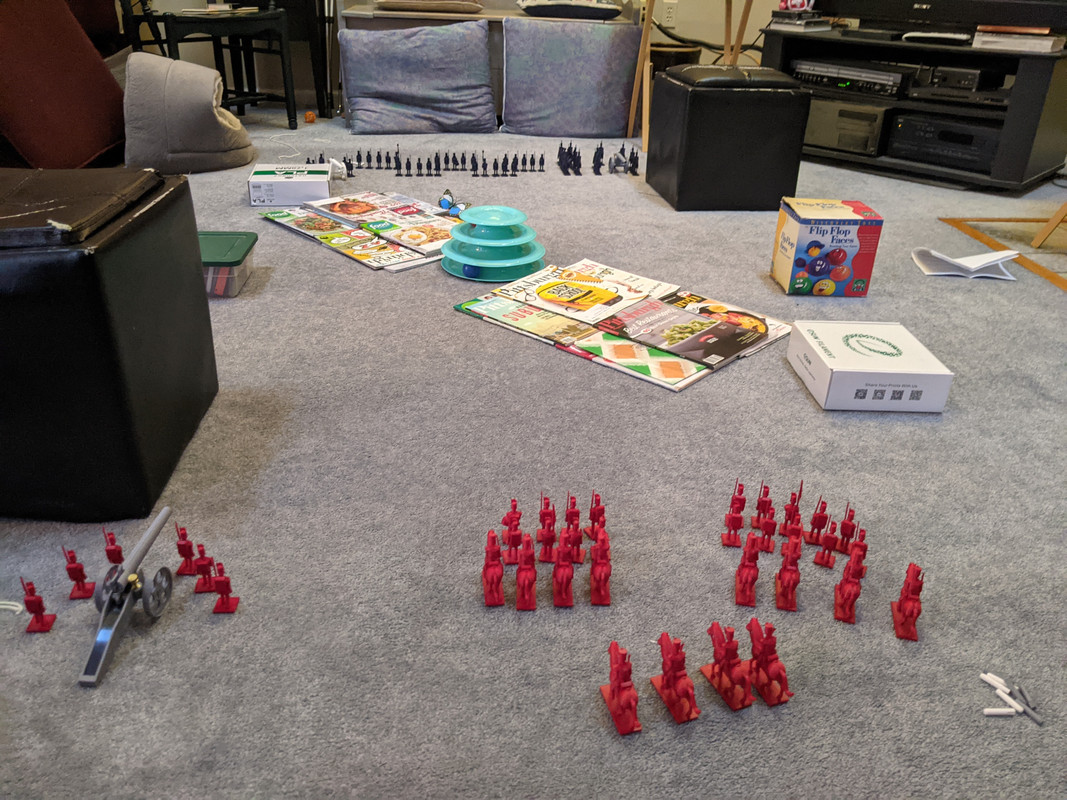

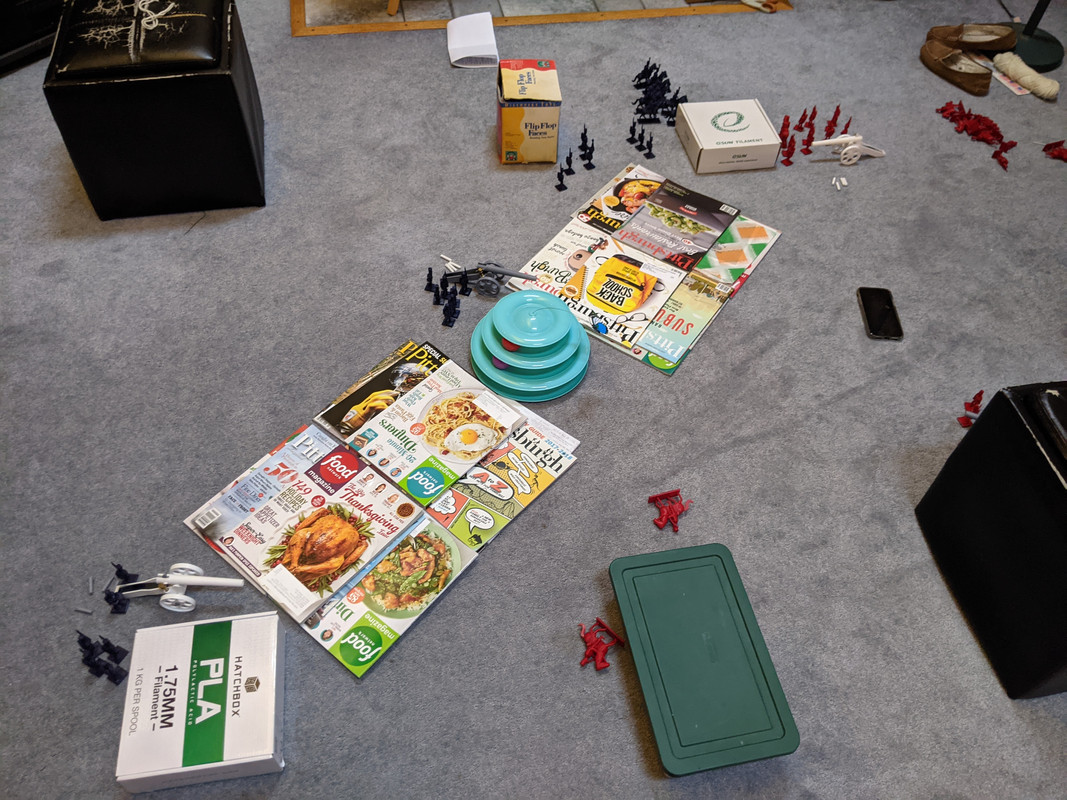

I have more or less decided to switch to a weak hand reload, favored by the other half of the top 20, for this season. First, a description; then, my reasoning.

The way I’m doing it, the weak hand reload starts the same as the strong hand: my left hand moves forward to the cylinder. At the same time, my right thumb hits the cylinder release, but my right hand otherwise stays put. My left fingers pop the cylinder out while I tilt the muzzle slightly upward, and my left thumb hits the cylinder release while my right hand starts to bring the gun down. My left hand leaves the gun and goes for a moon clip. By the time I have the moon clip in hand, the gun is directly in front of it, and the cylinder is at the same height. My left hand lifts the moon clip off the peg, moves it forward a hair, and drops it directly into the cylinder. On the way back up, my left thumb closes the cylinder, and my left hand rejoins my right on the grip. Here’s an example.

This method has one serious downside. Watch the example closely, and you’ll see that the gun is stationary for an instant, waiting for the moon clip. There’s only so much I can do about that.

Is it really such a serious downside, though? By my reckoning, the split time in the video above is about 2.5 seconds, and it’s not the fastest I can go. I’ve hit 2.0 a few times already, which is pretty sporty by wheelgun standards, and certainly unlikely to hold me back.

Suppose you aren’t convinced. There are some positives, too. First: it’s a very simple set of motions. Unlike the strong hand reload, there’s very little gun dancing to it. Gun tilts, gun comes down, gun goes up. Parvusimperator remarked to me that he doesn’t think about going fast, he thinks about doing things efficiently and with urgency. (It’s not his formulation, but I forget who he got it from. Scott someone? Steve someone? Ah, there it is. Scott Jedlinski.)

Second: access to the cylinder is clearer. The strong hand reload puts the grip in the way. Sometimes that causes trouble getting the ammunition in, and the path from the moon clip rack to the cylinder is necessarily a bit more twisty.

Third: I just seem to do it better. It’s hard to put my finger on exactly what it is. Clearer access to the cylinder helps make the worst case bobble not so bad. My left hand has direct access to the cylinder, and can more easily solve problems there. Another contributing factor is probably the cylinder chamfer job I had done. The mechanics of the reload, with the moon clip being so close to the cylinder, probably help too. My moon clips are relatively wobbly, which means they have the potential to flop as they drop from above the cylinder, and the weak hand reload drops them from closer. It’s also easier to see the positions of the chambers and align the moon clip correctly, since there’s no gun in between my sight line and the cylinder.

Or maybe I find the motions easier to pull off under pressure. The strong hand reload involves a lot of delicate manipulation of the gun, for the payoff that the strong hand gets to do the final positioning of the moon clip. The weak hand reload involves two or three big, simple movements, and one small one (the actual loading) that’s only moderately difficult. Whatever it is, I like this reload more, and so I think I’ll stick with it.

Reloads (ammunition)

Thanks to the fine gentlemen at the r/reloading subreddit’s Discord server, I came by a stock of 6,000 small pistol primers, which ought to be enough to get me through the 2021 season.

With components being scarce, I decided to get my bullets in bulk. A kind soul from the Brian Enos revolver forum sent me a little sample pack of Ibejiheads 160-grain coated numbers, and the Ruger likes them just fine. This was, I should note, back in October, and they’ve only just arrived. Components are, like I said, scarce.

Anyway, there are a few nice things about these particular bullets, but the most important one is that they’re the most tapered 160gr bullets I’ve been able to find, which makes them easy-loading. I’m fond of the ultra-heavy bullets: they only need to go about 800 feet per second to make minor power factor, which takes just a hair over three grains of Alliant Bullseye.

They’re still going in the same Starline .38 Short Colt cases, which I expect to last me years, and the load generally (heavy bullet, low velocity) has been my preference for the admittedly short time I’ve been competing with a revolver. The selection of the Ibejiheads bullets is just finalizing things. In the future, I might investigate a non-Bullseye powder—I’ve heard good things about Alliant Sport Pistol, especially with coated bullets.

Attitude

There are two components to this. The first is a change I’m trying to train. The second is an observation.

The change is this: I need to be looser when I shoot. It’s very easy for me to get tense, which leads to jerky motions, which means my reloads fall apart. I’ve been listening to a few podcasts on practical shooting of late, and one of them (the Shoot Fast Podcast, with Cody Axon and Joel Park) goes after the ‘slow is smooth and smooth is fast’ saying. I’m convinced that the saying is correct in some domains, but for shooting, I like the one the Shoot Fast guys allude to without ever outright saying: fast is smooth and smooth is fast.

I’ve verified this the only way I know how: experiments with the timer. The more I tell myself that a drill doesn’t matter, that I don’t care about the time, the better the time generally is, as long as I’m doing it at pace. With those results in mind, I invented a drill to try and burn the low-tension sensation into my shooting. I have my timer give me a start beep and do something fast (a draw, a reload, a double on a dry fire target). After I do the thing, I freeze, inspect my posture, and consciously relax and adjust how I’m standing or gripping, if needed, repeating until I’m relaxed while doing the thing.

Surprisingly, timed and regimented drills to enhance relaxation seem to be working, and fairly quickly. In combination with that, I decided to skip the par timer unless I’m actively working on speed. I still use a timer and still compare my times to the par times, I just have it set to shot-timing mode, to prevent getting in front of my skis while trying to beat the beeps.

And now for the observation, a closing thought for these almost-3000 words. Spend much time in practical shooting circles, and you’ll find a lot of big egos, and a lot of people correspondingly easily shaken by bad performances. At least, that’s what I take away from practical shooting podcasts. The ones I listen to put a lot of emphasis on the mental aspect of the game. I suppose that’s one of the advantages to being even-keeled by nature, and actively adhering to a faith that treats humility as just about the highest virtue. Those episodes are always slightly alien to me, which is to my advantage. It’s much easier to practice the shooting than it is to practice the mind games.

Goals

I wrote some about my goals in a previous post, and I can give updates on two of my 2021 goals already.

Short-term goal #3: end 2020 with a one-year stockpile of reloading supplies. I mostly did this. I have or can make about 3200 rounds of competition ammo, with the limiting factors being powder and bullets. Those are among the easier reloading supplies to find, so I’m not too concerned about my ability to use the primers that I have.

Short-term goal #4: work and shoot two majors. I’m on the list for Battle for the North Coast already, and may aim for the Buckeye Blast in June (if I want an earlier one) or the Virginia state championship in October.

And that’s about where things stand. I’m looking forward to getting this year rolling.