I wrote about Little Wars briefly in my last post, and thanks to a family get-together on Christmas Eve, I was able to play a small game for the very first time. I present to you the First Battle of Adam’s Ridge.

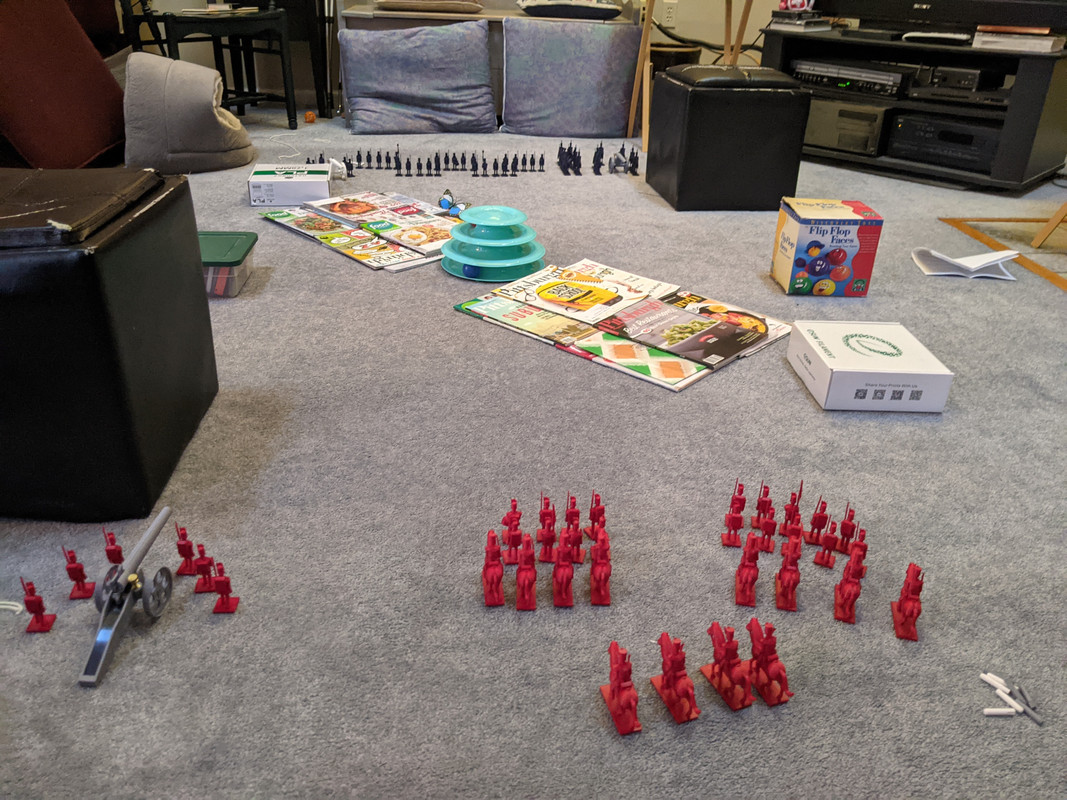

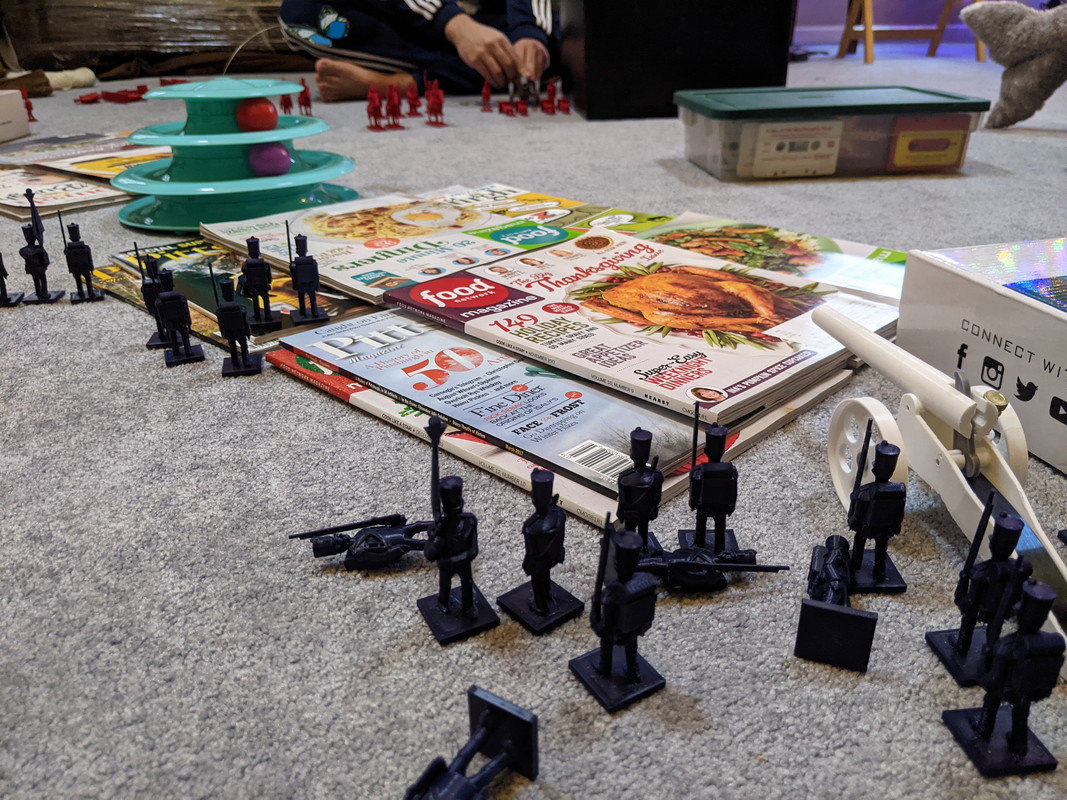

On the western edge of the field, my men, the blue army (French models).

Infantry in staggered ranks to make them a harder artillery target, with cavalry concentrated on my left.

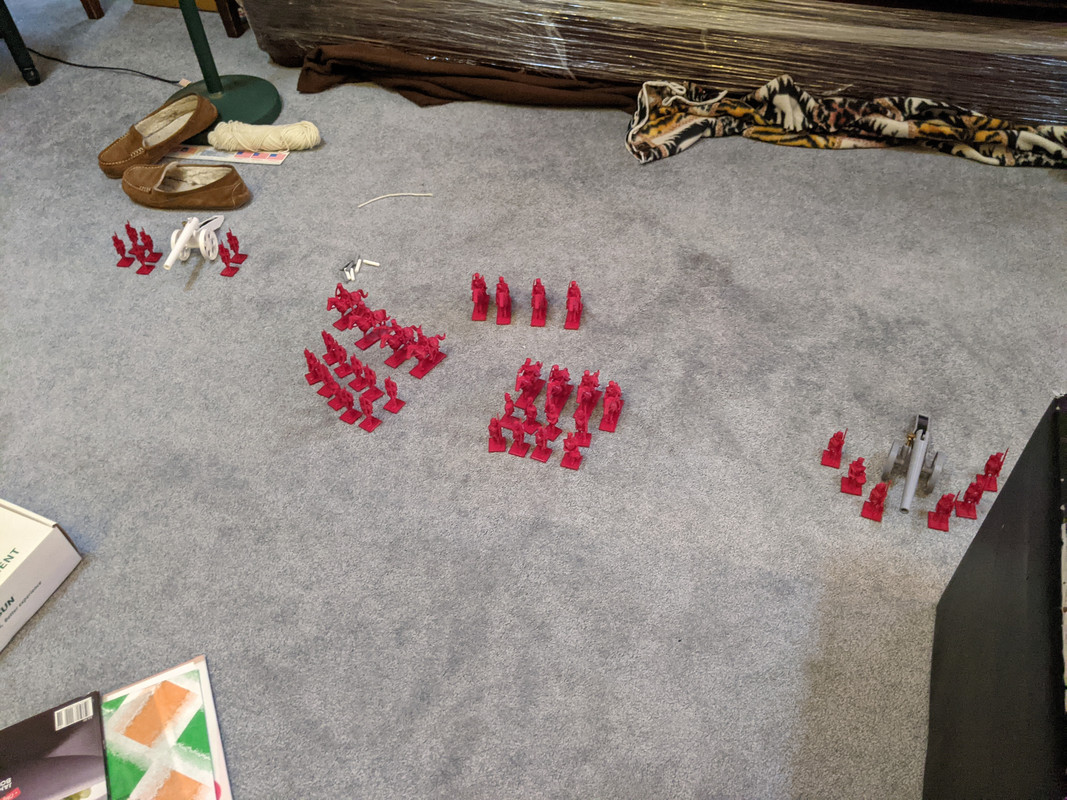

On the eastern edge of the field, my brother, with the red (British) army:

[

He decided to concentrate his forces in the center, perhaps to respond more quickly to any moves I made to the flanks.

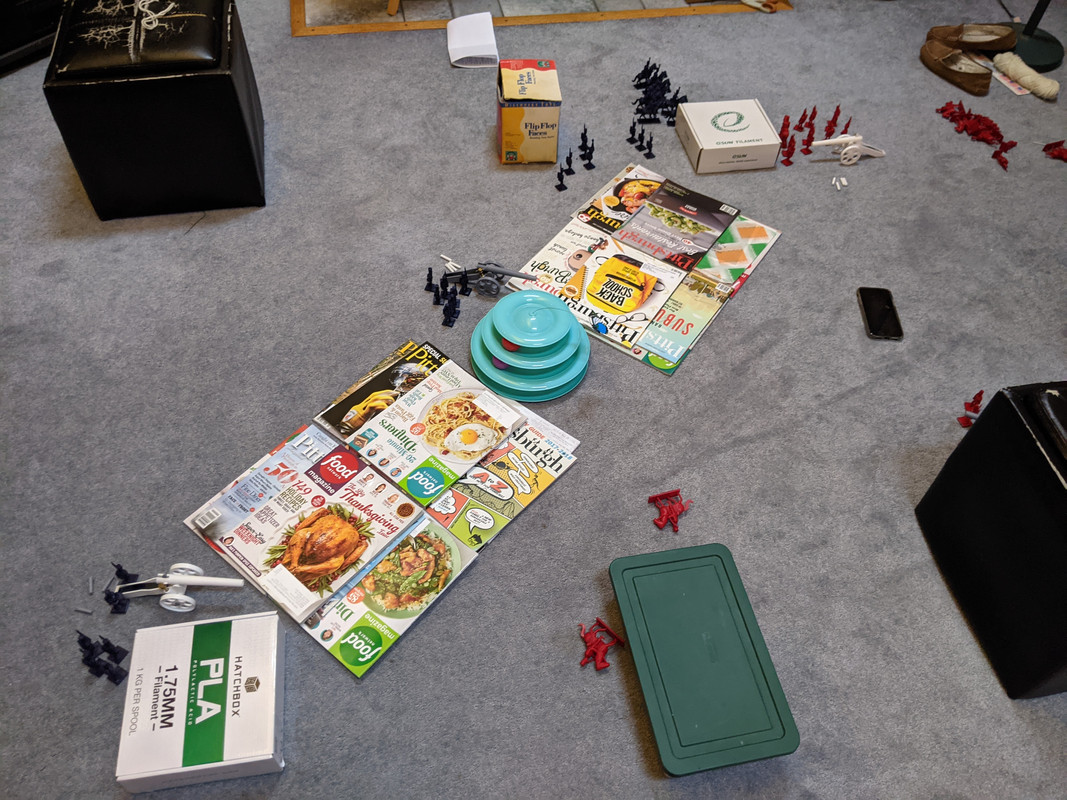

And now, the field, looking from east to west:

The central feature of this battlefield is Butterfly Hill. To its northeast and southwest runs the eponymous Adam’s Ridge, with the warehouse (the eSun filament box) at the northeastern end and the factory (the Hatchbox filament box) at the southwest end.

Due north of Butterfly Hill, to the right of the photo, is the fairground, and due south is the toy shop.

My brother won the toss and deferred, so I went first, advancing my cavalry force toward the fairground and moving my infantry in the direction of shelter under Butterfly Hill. I kept my right gun back by the factory, where it would remain for the whole battle, while the left gun moved forward with the cavalry.

Because the field was a bit small end-to-end, we decided to let the guns open fire after the first round, instead of after the second.

That brings us to about here, which is the end of the second round.

I’ve continued my advance toward the fairgrounds, and have reached cover from red’s guns, although they lost two of their number along the way. My men advancing on Butterfly Hill have lost several of their number to artillery fire, but my guns have done a respectable job in reply, dramatically thinning out the bunched forces in red’s center.

Bonus action shot, mid-round 2, as my brother aims a gun toward my artillery crew by the factory.

On to round 3!

I’m concentrating my cavalry at the fairgrounds, in the hopes of making a rush at red’s gun by the warehouse, and have moved my left gun up to Butterfly Hill, which is a dire threat to red’s center. Even long-range artillery can pretty quickly dismantle forces out of cover. This close, it’s easy.

To make it a little easier to move the gun to Butterfly Hill, my gun at the factory engaged the soldiers manning red’s gun opposite. If you look closely, you’ll notice it only has three men nearby, which means it’s out of action. I took that opportunity to send the infantry from Butterfly Hill on a march toward the warehouse: I don’t have enough cavalry there to charge the guns and win.

Round 4:

My guns did indeed exact a heavy toll on red’s center, but my force marching for the warehouse is now substantially smaller too. I think he had eleven men with his right gun (the one on my left), and I had eight cavalry behind the fairground at this point.

Red is attempting to get some cavalry around my right, behind the toy shop and the factory.

Notice also that red’s southern gun is out of action again. You only need four men near a gun, but having more seems to make artillery a lot more durable. Too, I think I probably failed to explain how guns work (four men within six inches, put two behind the wheels at the back of the trail after firing) to my brother, which led to his artillerymen being awfully exposed most of the time.

He has, however, moved his gun by the warehouse to the other side, where it can fire on my gun at Butterfly Hill.

Round 5:

Both of red’s guns are back in action again, and a fair number of my infantry made it to the warehouse alive—I have a slight edge in numbers there, but am handicapped by the fact that it’s a combined arms attack. The infantry are still two turns away, or at least most of them are. I think. Looking at the photo, I might have been able to drive home a successful, if costly, attack by looping the infantry around the south end of the warehouse, while the cavalry took the northern route.

In the south, the gun at the factory brought down two of the four attacking cavalry. The other two are slightly out of frame to the south.

Round 6:

I didn’t see the potential for a multi-pronged attack in the moment, however. My brother played it smart and moved his northern gun back a bit, so that it wouldn’t be put out of action in a melee around the factory, and would be in perfect situation to blast any cavalry who engaged.

At which point I looked at the field, felt relatively confident in my advantage, and decided to fall back, which may go down in history as a McClellan-esque bit of caution. We ended the battle by mutual agreement at this point: I didn’t feel like I had a sufficient force advantage to press an attack successfully, and he felt the same way.

Having both started with 68 points of troops, I finished with 50 to his 37.5, for a victory for me. By the objective we’d chosen, I think it would have been most appropriate for us to split the 100 victory points, which would have brought the tally to 100 to 87.5.

Now, on to reactions!

To start with, the rules seem to work very well. Wells obviously played a fair bit of this before he put his rules to paper, given how few the rough edges are and how well they generate something that looks like a real battle.

Notably, we didn’t get to try out the close combat rules: gunnery proved a bit too effective. We’ll probably play next game with one gun per side. Wells recommended one gun per 40 or 50 men. A slightly higher ridge probably would have helped too: it didn’t end up being an obstacle to artillery, whereas if we’d used a few more layers of magazines to build it, it might have, or at least provided some partial cover.

It may be a little too easy to silence guns, but that could also be my brother’s imperfect grasp of the artillery rules. The guns performed well, firing with plenty of power to bring down soldiers and cavalry alike. I think the best shell of the game took down four? I might experiment with a slightly thinner spring, even—I need to order a batch of boxes anyway, since the filament boxes don’t quite fit the taller sorts of soldier, and I could always add spring steel to a McMaster-Carr order. One downside is that the late prototype guns (the ones printed in white plastic) don’t have quite the right tolerances, so their wheels were frequently falling off. Less than ideal. Too, gray is a very bad color for the shells. The next batch I do will probably be in white or red—something to stand out against your average carpet.

In spite of some initial doubt, we ended up playing with the prescribed three-minute time limit. It did its job perfectly: we didn’t have a ton of time to sight in guns, and when we did to ensure we got hits we needed to, we were short on time to do other things. I had to skip moving men once or twice, and made some bad movement decisions a few times because of the clock. A brief aside: Wells wrote about having to find a big clock with a second hand, or wrangle a visitor with a stopwatch into refereeing, which speaks to a timekeeping problem ubiquitous cell phones have relegated to history.

Even though we didn’t get to exercise the close combat/isolation/surrender rules, I was thinking about them as the game was ongoing, and they made a lot of sense: most of the melees that might have happened involved unsupported forces, and would have yielded some prisoner-taking. Given the situations we encountered, it seems like they’d work substantially better than I would have guessed.

Finally, we forgot or misapplied a few rules, but I don’t think it had a serious effect on the outcome of the game. Neither of us were playing the tryhard, but if someone were to do so, I think insisting on rules-following would make it relatively resistant to munchkinry.

All told, an extremely successful first battle, and I suspect we’re going to have a second one today.