We return with another two-year stretch. (Or, at least, hopefully two years. I have company coming over on Saturday, which is my usual play-the-game day. We’ll see how far I get.)

Goals for this entry include designing a battlecruiser (circa early 1905), keeping the naval budget more or less balanced, rebuilding our older battleships to use better fire control, and pushing for moderate tensions with Italy and/or Austria-Hungary to permit us to build more ships.

June 1904

To start with, I place a few ships into reserve fleet status, which cuts their upkeep in half but reduces their maximum crew quality to ‘Fair’. (Ordinarily, the maximum is ‘Good’. I don’t recall offhand if specialized training increases the maximum to ‘Elite’.) Given that I don’t expect any wars in the immediate future, we can afford to.

Another Francisque-class destroyer comes off the ways, completing our initial buy of seven. I could scrap some of the Fauconneaus, but destroyer upkeep is so cheap that it’s hardly worth the effort.

Finally, I start the rebuild process for the La Républiques, updating them from central rangefinding to central firing. The history of battleship fire control is the history of centralizing more parts of the process. Central rangefinding moves the rangefinding away from the individual guns and to a central position, which can be elevated above the guns’ smoke and also made more delicate and (therefore) more precise.

Believe it or not, this photograph is of a ship firing using smokeless powder. Clearly ‘smoke less’, not ‘smokeless’.

Central firing moves the triggering of the guns to a central location, which helps eliminate errors in timing.

Finally, director firing lays the guns automatically—the turret crew no longer controls azimuth and elevation.

August 1904

July passes quietly. The British are still building pre-dreadnoughts—and pre-dreadnoughts which will be a much greater liability in the future naval era than our Tridents.

Italy, too, is refitting its battleships with central firing.

October 1904

The first La République completes her refit.

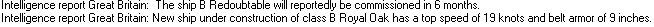

At the same time, the first design studies on the Duquesne-class battlecruiser begin.

Tallying the votes across all the places where this AAR is running, German-style battlecruisers won the day. This 24-knot ship mounts six 11″ guns, a secondary battery of 6″ guns (+1 quality), and a tertiary battery of 2″ guns (+1 quality). (A gun of +1 quality is approximately equivalent in range and penetration to a 0-quality gun with a caliber one inch larger.) She has a 10″ armored belt, and tips the scales at a hair over 18,000 tons.

In other news…

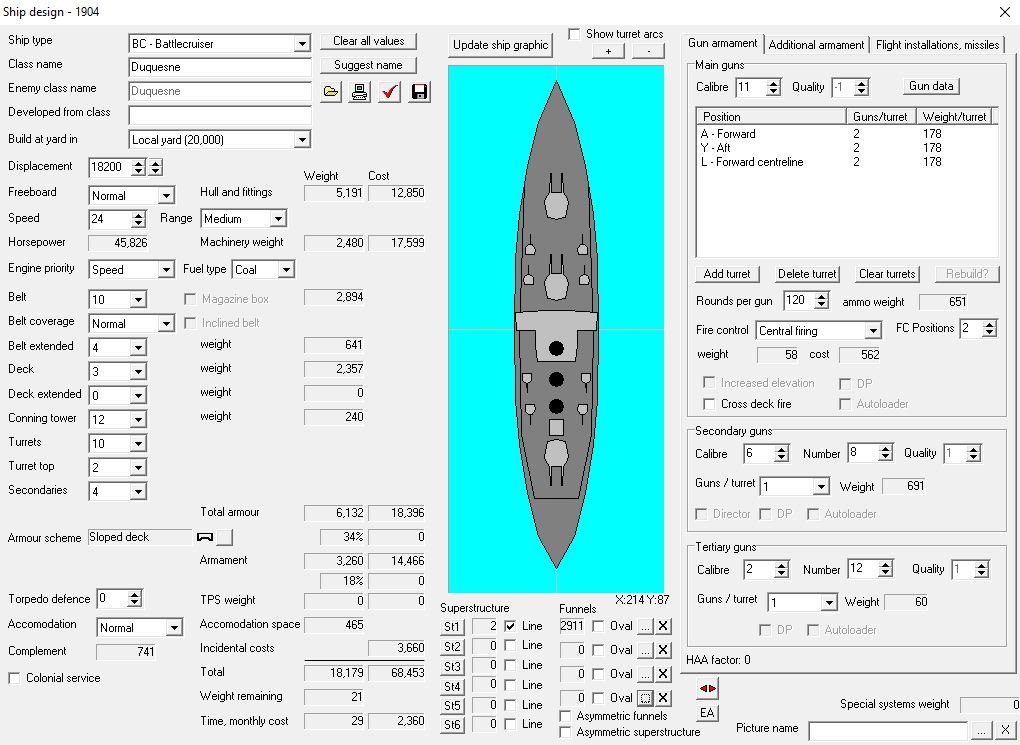

I was flipping through the almanac to see where we’re going to land in the dreadnought race (second to get one under construction, it looks like!), and found that the Austrians call this a battleship. We have to have a war with them.

January 1905

We elect to refit the Tridents with central firing before they even come down the ways, which saves us a rebuild cycle on them.

February 1905

The first Duquesne‘s keel is laid. She should be ready in early 1908.

The lack of any budget-increasing events has been a bit of a bummer. I’m considering mothballing some of the light cruiser force to free up some more money. As it is, we’re building one Trident, one Chauteaurenault, one of the new Isly light cruisers, and one Duquesne, and still losing money. Ideally, I’d be able to rebuild a La République with better fire control while still keeping up on the dreadnought program.

Advanced gunnery training is a stretch goal, but the budget is too tight to permit it right now.

March 1905

Given that our light cruiser fleet is still enormous compared to everyone except for Great Britain, I decide that putting a few in mothballs (it’ll take about a year to bring them back to combat strength) is acceptable to keep the battleships rolling. Especially now that we’re building replacement fleet light cruisers, keeping all the Tages at 100% operational capacity isn’t as important.

April 1905

A new government wants to cut arms expenditure. I protest loudly and receive a small bump in the naval budget. There are now three La Républiques rebuilding at the same time. (Also, it’s a little cheaper than it appears at first—you don’t pay regular maintenance on ships under rebuild.)

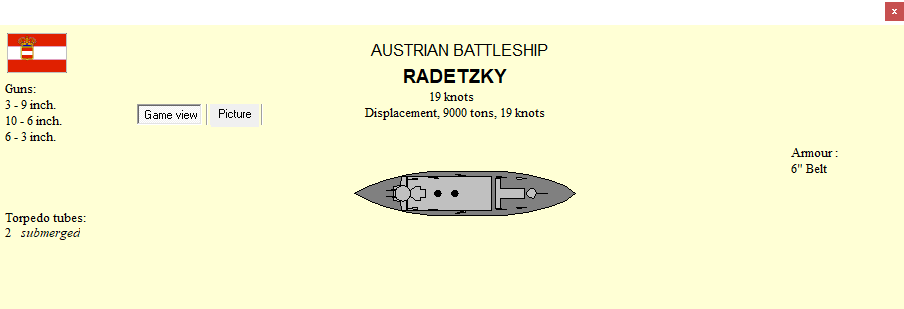

June 1905

Nothing bad can possibly come of this. We stand behind our ally and reap the budgetary rewards.

Upside: we can afford the refit on the rest of the La Républiques. Downside: tensions are up with Germany, who we really can’t fight on even terms.

September 1905

Thinking they’re being helpful, the government votes to increase naval spending given tensions with Germany, which… raises tensions with Germany.

October 1905

The French public raises 50 million francs for a battleship. We lay down one Duquesne because our last pre-dreadnought Trident completes, and one Duquesne with the funds the public so helpfully collected for us.

Six-gun ships are nice, but I’d like to push to eight soon.

November 1905

Thanks to our dreadnought-building program, Britain is forced to raise spending to keep its navy preeminent.

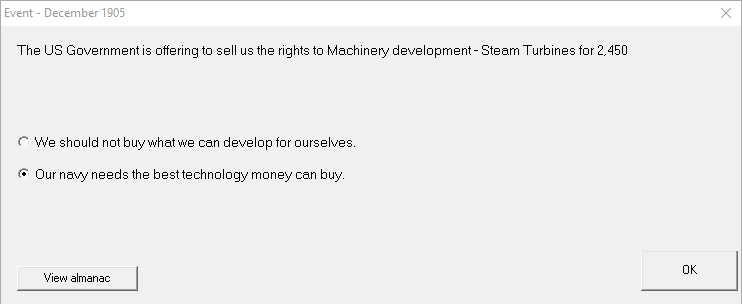

December 1905

The Americans sell us the rights to steam turbine technology, which we’ll take, thank you very much.

Propulsion is one place where Rule the Waves elides a little bit of detail. Steam turbines, in the game, represent a simple decrease in the weight of a ship’s machinery. This is a bit of a simplification.

Shipboard steam propulsion starts with evaporators. Salt, as you’re probably aware, is corrosive, and salt and steam are worse than either in isolation. Marine boilers and condensers demand fresh water, so steamships have to produce fresh water from the materials at hand—heat and seawater. Evaporators distill seawater to fresh water, which is then fed into the boilers.

Boilers do what they say on the tin, turning fuel (in this era, coal or oil) and fresh water into high-pressure steam. The volume of steam a ship’s boilers produce determines how fast it can turn its engines.

In our early-20th-century timeframe of interest, there were two types of engine of note. The first is the multiple-expansion engine, most frequently the triple-expansion type. Steam flows into three cylinders of increasing size, driving a piston in each cylinder. Increasing the size of the cylinder at each step means that each cylinder generates substantially similar force—as the steam flows through the engine, its pressure goes down, so giving it a larger area to act on counters that effect.

The second type is the steam turbine, demonstrated in dramatic fashion by the Turbinia, which showed up at the Navy Review during Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and proceeded to outrun the fastest vessels the Royal Navy could send to chase it down. From this beginning, turbines eventually made it into most of the world’s warships by about 1910. (At the end of this tangent, I actually back up my assertion that the elision of detail is important.) Like all turbines, steam turbines are essentially pinwheels writ large—blow through it, or force high-pressure steam through it, and it rotates.

Finally, after steam passes through the engine, it arrives at the condensers, which turn it back into fresh water for recycling through the system again. Reusing water means that the evaporators don’t have to work as hard (although ‘not as hard’ still translates to ‘tons per hour’, in this context). When condensers break, steam-powered ships are unable to generate as much steam (since they have to wait for the evaporators, rather than using water they already have), which slows them down.

Anyway, all that to say that the US Navy, in the early days of steam turbines, waffled between turbines and the older triple-expansion engines. Why? Because turbines are only very efficient near full power, and triple-expansion engines, though larger and bulkier, can run at cruise power much more effectively. As late as USS Oklahoma (laid down 1910, commissioned 1916), the Navy built ships with triple-expansion engines, because for they had better range for a given weight of fuel, and we Americans didn’t build fast battleships until the North Carolina-class in the late 30s. Other American ships (and other shipbuilding nations) experimented with a smaller cruise turbine, which would push the ship at cruise speed when running at full power.

In Rule the Waves 2, you don’t get the choice. You just pick a fuel type and an engine focus (from Speed, Reliability, or neither).

February 1906

An uprising in China presents us with the chance to reduce tensions with Germany, which we gratefully take.

May 1906

Germany takes advantage of our softness and sends a force to occupy Angola, which produces very little of note.

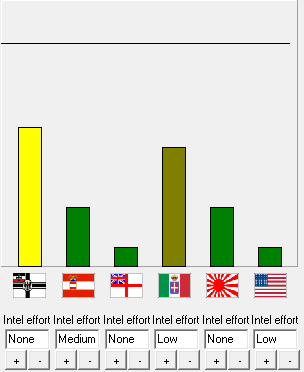

Two-Year Report: Diplomacy

Aside from the aforementioned tensions with Germany, things are quiet enough. Italy is making noise again, and building a few more battleships to boot.

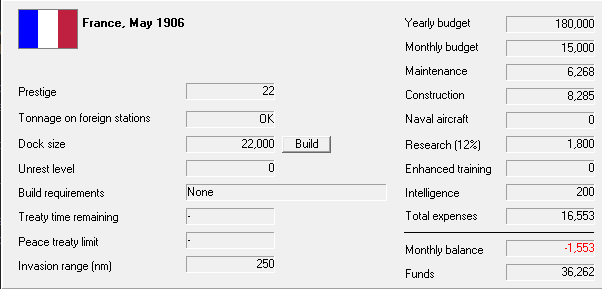

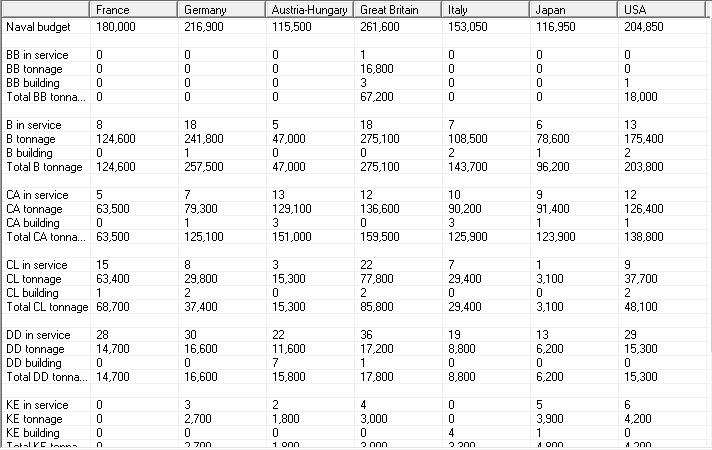

Two-Year Report: The Fleet

Speaking of which, the fleet report! We’re currently operating at a deficit of 1,553 kilofrancs, but the first batch of ships will finish before we run dry (a new light cruiser and the first Duquesne).

Right now, we look pretty good in the Mediterranean Throwdown Power Rankings. We have a small edge over Italy right now in battleships, and given that our battlecruisers are armored well enough to stand in the line of battle, we’ll maintain that edge even given the predreadnoughts they’re still building.

We’re behind in armored cruisers, as ever, but the battlecruisers are, in part, intended to fix that.

Our huge superiority in light cruisers gives us advantages in the commerce raiding game—we can detach a bunch of them to go sink merchants without much fear of losing them or falling behind our chosen opponents in attached-to-the-fleet strength. Ditto destroyers; they’re a great way to fill the trade protection quota while corvettes build. On the downside, we’re a little behind now on submarines. Should we think about building more?

That said, I think there might be room in the schedule and the budget for an updated Chateaurenault class. The Gueydons, which are filling the larger part of our foreign obligations, are expensive to maintain, especially away from home waters. A class of foreign station light cruisers, with medium or long range and equipped for colonial service (the latter makes a ship count for 150% its tonnage when determining how much you have vs. how much you need on a foreign station), would fill the gap nicely. We could mothball or even scrap a Gueydon or two, and put the savings into more shipbuilding.

Another option might be to put some money toward a class of coastal monitors—ships with, say, a pair of large-caliber turreted guns, low speed and short range, and a ton of armor. With some of those, we could limit the ability of foes to blockade our North Atlantic or Mediterranean coasts without diverting units from the main fleet.

Of course, there’s also room for a class of proper battleship-style dreadnoughts—something with 22-knot speed, a bit more armor, and 8 or 10 guns. (The only reason the Duquesnes are six-gun ships is because we don’t have the technology yet to put more than three turrets on a ship such that all of them can fire at a broadside enemy. There are two technologies that allow that: 4+ centerline turrets, and cross-deck firing for wing turrets.) These three Duquesnes will likely be the only three, as well, given that we have steam turbine technology now, and that leads to large weight savings at higher speeds.

Of course, if we wanted to stick with a six-gun ship, we also just developed 14″, quality -1 naval guns, which would go nicely on a dreadnought.

Meta

I won’t be able to do my usual weekend play-through, so next week’s update might slip a bit, or perhaps cover less time.